Said Abu Shakra Gallery Manager

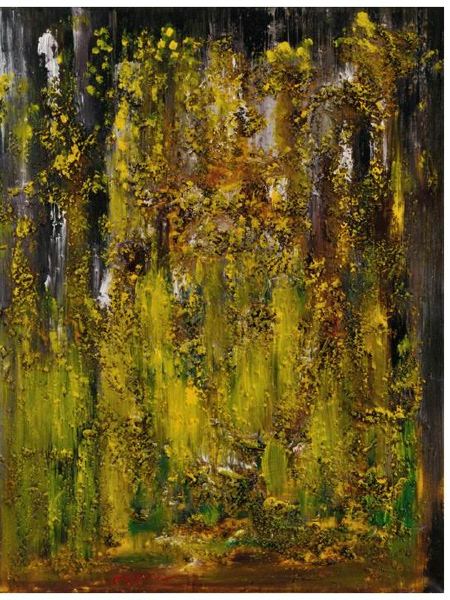

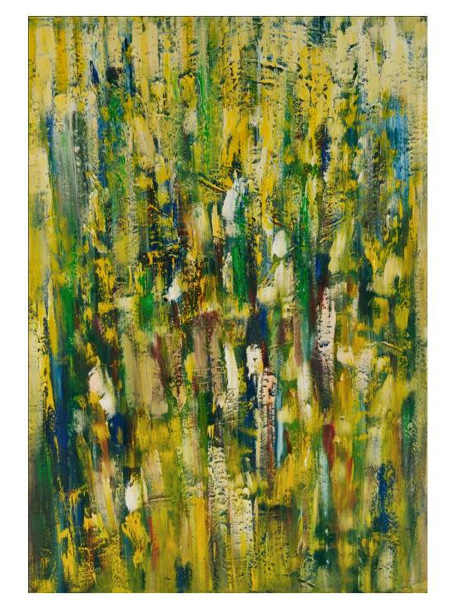

Splotches of Colors as the Blooming of Spring

Usama Said, his family’s eldest child, is a member of the first post-Nakhba generation. About 10 years prior to his birth the family experienced a tragedy that totally crushed it to bits. In Said’s words:

“Rumors had spread of the execution of three men in the central square of Nahaf, where the fam- ily lived, by Hagana forces, and my grandfather, Abdullah, decided to smuggle his three eldest sons out of the village and to keep only his younger children at home. Grandfather feared that the elder boys would be murdered, but he instructed them to return once things quiet down and it would be clear how the winds were blowing. However, when the war finally ended, soldiers were posted along all of Israel’s borders, and the connection with the mature sons was lost forever.”

Grandfather Abdullah’s fateful decision was of tragic consequences for the Said family. The three eldest sons, the source of the family’s strength, left the village and made their way northwards together with swarms of other refugees, reaching Aleppo, Syria. The family, and Grandfather Abdullah and Grandmother Fatma in particular, were engulfed in feelings of sadness, gloom, sor- row and mourning. The grandmother couldn’t stop crying the rest of her life, going blind and dying of heartbreak; the grandfather, who was unable to escape the weighty burden of responsibility for the decision that had led to the loss of the three children, used to say: “I turned my sons into refugees in a foreign land, with my own hands.”

The birth of Usama was accompanied by a sense of great hope, as the family saw a sign of renewal in him, compensation of sorts for its great loss. From the day Usama was born, his life and that of Grandfather Abdullah were intertwined. The young child spent most of his time growing up, at his grandparents’ house, and Abdullah would share memories with his grandson of his violence- torn past, but also his hope, which found expression in working his land and his love for nature:

“I roamed free on Grandfather Abdullah’s large plot of land, known as ‘Nasab Jassir,’ from just about as early as I can remember,” Said recalls. “I would accompany my grandfather as he plowed and as he reaped, and I would serve as a sentry in the fig and plum orchards, after I had finished school for the day. That is how I became connected to land and to nature. I could identify birds by name, I was familiar with every rock on grandfather’s land and I loved the changing seasons: summer; the rainy winters; spring, the season of flowering, and autumn, of course. It was love, and I still can remember the blue skies, the brown, tilled fields and the blooming of spring, needless to add, with its carpet of multiple colors, which covered grandfather’s land and instilled hope and love in us.”

After Said had completed his high school studies, he parted ways with his grandparents and trav- eled to Germany for further education. A few years after he had moved away, he was told that the two people that had had such a great influence in shaping his personality and identity had died without his being able to be by their sides in their last moments and without the opportunity for him to mourn their deaths in a suitable way.

Usama Said made an effort to trace the steps of his lost uncles, Omar, Mahmoud and Moham- med, in Aleppo, and those of hordes of other refugees in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and all over the world, and he would ask all the people he could find, to tell him their personal stories. Many layers are evident in his work, and the expression of personal feelings is but one of them. Using his art, he attempts to heal wounds that have been part of him for many years, deal with the subject of memory and forgetfulness, to let his personal and collective emotions and feelings gush forth and to lay them out for wide-ranging discussion. It was also his way of paying his grandparents back for the life they gave him. Grandfather Abdullah and Grandmother Fatma did not live long enough to see their first grandchild to be born after the Nakhba, return to the village with pride to instill a new spirit of hope in the mood of gloom that had enveloped them when they were alive.

“It was so natural for me to study Art. Nature, with all of its powerful energies, still reverberates in me. Art was - and for me it still is- the tool by means of which I am able to let the memories of my past gush forth, and this is how I relate my personal tale. My own story embodies the collective narrative of Grandfather Abdullah, Grandmother Fatma and their entire generation, the land, and the past that has been eradicated; the untold story and the people that left and will never return.

Usama Said’s retrospective exhibition reflects the artist’s creativity and his frequent peregrinations over a 30-year period. Like other Palestinian artists of his generation living in Israel, Said also ap- pears to be coping with a deep crisis of identity. Molded in the course of his childhood with stories from the past and with an enormous love for home and the land, he took this legacy with him when he left for Germany, where he also started a family, before returning to Nahaf as a strengthened individual with the ability to express himself with clean-cut lucidity. He has followed this path ever since, and his works deal with the issues that have bothered him all his life: alienation; land and its expropriation; separation; identity.

Dr. Nava Sevilla Sadeh, curator of the exhibition, who became familiar with the Said’s personal history, has chosen wisely in calling it “The Blooming of Spring” - a headline expressing the artist’s great love for nature, along with the memories of the past and life’s hardships, and with echoes and hints of the “Arab Spring.”