Land Work

Temporal Materials in the Oeuvre of Osama Said

Ami Steinitz

Interlude

In the autumn of 1981, Osama Said reached West Berlin and was admitted to the Academy of Arts in the divided city. Said was born in 1957 in the Lower Galilee, in a thick-walled hut of dried mud in the old center of Nahf village. Divided life in its Arab-Jewish,Palestinian-lsraeli, traditional-modern iteration was the reality that he knew from early childhood. His house bordered on the village mosque; livestock spent the night corralled on its ground floor,below the bedroom floor. Said remembers his grandmother carrying him on her back as she and her friends clustered in the narrow alleys,chatting and sharing figs. This bucolic material legacy would change perceptibly soon afterward,when the family moved from the dried-mud house to a new one built of poured concrete,the modern way.

The development of the Palestinian village and its transformation into an Israeli town is linked to the Nakba and the 1948 war.Refugeeship,land expropriation, and the transition from agrarianism to wage labor were the fate of many families,including Said's(Kimmerling, 149). Said's grandfather sent three of his older sons to Syria until the storm could blow over. When the war ended,the frontiers between Israel and its neighbors were sealed; the sons, unable to return, settled in Aleppo, Syria (Jamal,48). Although Osama would never know his uncles, his grandmother's anguish and his grandfather's pangs of conscience seared the pain of the war into his consciousness.

The Said family's new house was built on the edge of the village, among fields and orchards close upon the Acre-Safed road. The Jewish city of Karmiel was established on the southern flank of the highway in 1964. The transition from a dried-mud house in the middle of the village to a modern residence facing a Jewish city under construction, inspired by the International style in architecture,signified the difference that took shape between a material culture with a traditional link to nature and a modern urban environment that affects the life cycle from top to bottom.

In Said's childhood,fields and trees still enveloped the family home and Said drew shapes in the soil using sticks and stones, lay down on clods of soil in the furrows,and imbibed them into his senses.

“Land was my first paper,” he relates, “and my contact with it made me feel whole. Whenever I wanted to feel good, I drew simple images and forms in the soil.[...] I etched them and then climbed the olive and pomegranate trees to get an overhead view and decide what should be changed and fixed.At first I tried to draw my mother's face; she spent much time away from home because she was working in the field. I drew animals, a dog or a cat, and was allured by the shape of the olive leaf. I tried to copy nature accurately.The village didn't have children's games like Lego and cars back then, so I busied myself outdoors, in the mud. [...] At school the children called me the painter;the math teacher, an amateur painter, gave me special treatment.[...] My talent was recognized and women in the village occasionally asked me to draw the outlines of images on fabrics that they were embroidering."

Said took his first art studies as a high-school student in the mid-1970s. The newspaper Al-Ittihad ran a notice about an art class that Abed Abadi would be facilitating in Kafr Yassif.Al-Ittihad,the Communist Party newspaper lest. 1944) that stewarded the Rakah-Hadash party from 1965 onward, was the first Arabic-language vehicle that had begun to mark important events in the history of Israel's Palestinian minority (The Seventh Eyel. The predominant personalities in the paper were the Arab leaders of the Israel Communist Party,including Tawfiq Toubi,Emil Habibi,and Emil Touma (Caspi,Kabhal. By reading Al-lttihad as a teenager, Said was exposed to the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish and Samih al-Kassam,among others, and to the paintings of Abed Abadi (Said). In 1964,the party sent Abadi to study graphic design and art at the high academy for the arts in Dresden, East Germany.He would spend seven years there (Ben-Zvi, 2010: 43). In 1972-1982, Abadi was the graphics editor of Al-Ittihad and the literary journal Al-Jadid.His art works and those of artists such Burhan Karkoutly,a Syrian,appeared in the press and in books (Said). The two of them mated writing with visual art and instigated a discourse of identity between text and its symbolic visual representation (Bulata, 1990;Ben-Zvi,2009,64).Abadi's course focused on painting inanimate nature and reproducing nature in colors and pencil (Said).

Mastery of the basics of academic painting and production of Social Realism works in the figurative abstract style-the kind that were published in Al-Ittihad-dovetailed with the perception of teaching and art in East Germany and the Communist Bloc (Abdullah: 15). They were countered by trends of abstract and conceptual art that had evolved after World War Il in America and Western Europe,which had attained an international status that gathered strength after the Soviet Union began to fall apart in the 1980s |Abdullah: 28).

In March 1976, the Palestinian community in lsrael declared a day-long general strike and held protest demonstrations in response to the government's decision to expropriate 2,000 hectares of land from Arab citizens in the Galilee. As the protests proceeded, military and police forces clashed with the demonstrators, leaving many injured and six dead. Said,who took part in some of the protests, was familiar with the process of putting up the monument that Abed Abadi and Gershon Knispel had designed. The commemorative work was dedicated in Sakhnin in March 1978 (Ben-Zvi,2010).These events sharpened Said's realization that art is more than the ability to copy. Thus he began to deal with the occupation and refugeeship that he had known from his childhood in Nahf (Said). In the 1970S, Social Realism still reflected a sense of mission by participating in the ongoing struggle between socialism and capitalism for justice and equality.The steadily crumbling relationship between the socialist ideology and the dictatorships, however,robbed the mission of its content.

The young generation of Palestinian artists in Israel who had begun their studies in the early 1980s did not resort to places of study in the Eastern Bloc. Instead, it was influenced by modern art, which enjoyed greater freedom,left room for criticism, and made allowances for creative openness.Even though art schools in Israel and the West do not articulate the Arab cultural identity (Ben-Zvi, 2009, 63), artists such as lssam Abu Shakra, Farid Abu Shakra, and Osama Said applied to them due to the far-ranging artistic experimentation that they allowed.

“Back in high school,” Said relates, “I'd already decided to be an artist and rejected any possibility of practicing another occupation. [...]When I finished my studies, my father sent me to be tested for the post of manager of the Barclays Bank branch that was about to open in the village, and I was chosen for the job. I knew math and loved to read; that gave me a broad general education. I read books by Maxim Gorky and Fyodor Dostoyevsky as well as Arabic literature. Father, who worked as a teacher, had a big library and I also borrowed books from a mobile library. I knew the books of Tawfiq al-Hakim,Najib Mahfouz,Ihsan Abdul Quddous,Ahmad Amin,Garcia Márquez,Victor Hugo,and Ernest Hemingway,and the poetry of Garcia Lorca and Pablo Neruda. When the bank branch in Nahf was opened, I quit my job there because I'd chosen to be an artist. The manager of the bank in Acre ripped up my letter of resignation and tried to talk me out of it. At home,they pressured me too. I fled to Jaffa and moved in with friends who worked in restaurants until I moved to Jerusalem and tried, unsuccessfully,to enroll at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design.”

It was in Jerusalem that Said encountered modern art history.He spent hours and hours at the lsrael Museum,examining for the first time original works by Picasso,Braque,Modigliani,and Chagall.He found the varied Modern attitude toward the figurative image impressive. And he bought his first art history book, Herbert Reed's History of Modern Painting, published in Hebrew in 1971. Thus he became acquainted with the German Expressionists and with Otto Müller,Karl Schmidt-Rottluff,and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner of the Brücke group. The strange bold colors, the unrestrained brush work, the straight lines, the crisp outlines of the bodily images and manifestations made an impression on him. One of his first stops in Berlin was the Brücke Museum in the city's Dahlem quarter.

Art in a divided city

The broad ambit of modern art, the role of Social Realism in it, and the line that separated East from West and personal choice from social obligation were engraved into him even before he reached Berlin. Said had first gone to Frankfurt,where by chance he encountered Burhan Karkoutly, whose work he knew from Al-lttihad. Karkoutly urged him to take lessons with the fellow Syrian, Marwan Kassab-Bachi,who had reached West Berlin way back in 1957, did his studies there,and then taught at the municipal Akademie der Künste (Academy of Arts). Accepting Karkoutly's advice,Said relocated to Berlin and studied with Marwan for six years. The culture and language that he shared with his mentor eased his entrée to the German art world, where Marwan had been active for many years. It opened doors to meetings with Arab artists, some of them exiles, such as the poet Adunis and the author Abdul Rahman Munif, and helped him to develop his artistic career. Partitioned Berlin was nothing like Paris, where Said had originally thought to study.

The world war and the genocide that the Germans had perpetrated had left the city divided as a palpable relic of the disaster that shattered the dream of modernity, progress, and enlightenment. Berlin had become the focal point of a cold war between West and East, between socialism and capitalism,between a free society and dictatorship. Said had made his way to Berlin at an especially historical moment, with Modernism on the decline and Postmodernism taking shape(Huyssen,1984,7-8).After World War ll,the communist East and the democratic West had clashed over the question of revitalization.Those in charge of East Germany inveighed against "degenerate" Western Modernism and declared Social Realism the official anti-Fascist style (Huyssen,2010).In West Germany,those in power were eager to thwart any reversion to nationalism. They considered the art of totalitarian East Germany oppressive and negative and saw International art,lacking in signifiers of place as indicated by its American abstract origin, as something positive (Stiassnyl. The growing weakness of the Eastern Bloc in the 1970s and 1980s neutered the confrontation surrounding the dream of Modernism of the brawls that once characterized the rivals. However, it left behind a deeper existential mystery in respect of the question of modern governance. Whereas myths in premodern culture sustained traditions in order to enforce social restraint, the modern dream-political,cultural, and economic-expressed a utopian aspiration for a social reality that would crowd out existing forms. These sweeping utopian dreams took a dangerous turn when the ruling forces mobilized their driving energies for action against the public that they were in fact supposed to serve (Buck Morss, x-xi).

Said devoted his initial stay in Berlin to studies and visits to museums and exhibitions.At the Neue Nationalgalerie (New National Galleryl, he encountered the works of Matisse and Cezanne and attended a great retrospective exhibit of Max Beckmann in 1984. The varied approach to the figurative image and the unrestrained media of material expression that had impressed him back in Jerusalem now energized him and prodded him to an eruption of creativity that became a personal happening in itself. The grand dimensions of the works in which he experimented demanded broad brush strokes, massive blocs of material, sprawling surfaces, power and delicacy, thick layers and transparent thinness, drawing, color, use of paper and canvas along with readily available materials, brushes, and sticks, as well as handicraft and sculpture.

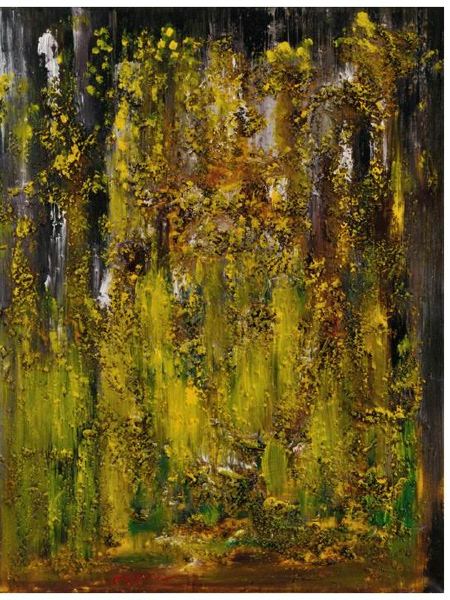

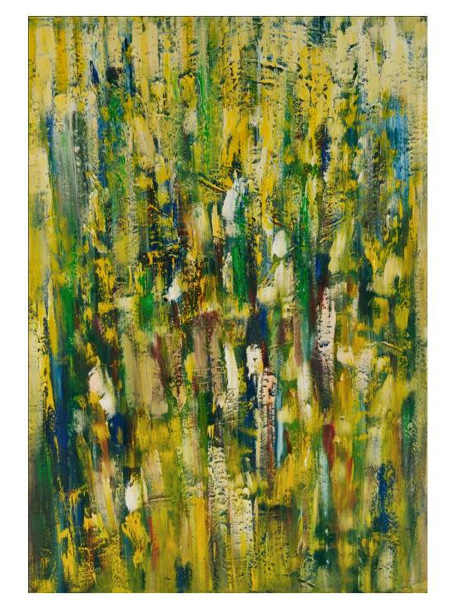

Said's thirst for an abundance of art seemed like a chaotic passion but was actually a reversion to the materiality that typified the land-works of his youth. Again he derived pleasure from rich contact with material,the nexus of material and tradition, intimacy with nature, and the humanness expressed by all of them. Art became a material field of action that likened the chunks of soil, which had served him as a platform, to the images that he had drawn in his childhood. The black lines that demarcated surfaces in Beckmann's triptych paintings,the straightness and the yearning for nature of the works of the Brücke group, Cezanne's formal mass, Matisse's crimson surface, the internal tension and fracturing of forms in Appel and Asger Imembers of the COBRA groupl, the bodily movements in Jackson Pollock's and Willem de Kooning's action paintigs, the paint surfaces of Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko of the New York school, the oeuvre of Francis Bacon of Britain; the German Neo-Expressionism of Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz (Marwan's friend);and Classicalworks of Giotto and Titian-together steered Said to a new Postmodern intersection between tradition and progress. At this intersection, he was able to touch the modern pain and contemplate humankind's future by arranging the conceptual outreach of material to tradition.

The current exhibition sheds retrospective light on the cyclical material evolution with which Said mates matter with life-matter,introducing pain to humanness, the political to the metaphysical, premodern tradition to the Postmodern malaise. In his opuses, his work with material reflects a slow,non-revolutionary, conceptual and practical oscillation of "land work"-an oscillation that pulses between the furrows of the emotional, sensory, sensual, historical, cultural,and existential meaning of the touch of the human hand on material and stimulates primeval responsibility for it-a movement that crosses from painting with material to the compounding of materials, to sculpture, and now to installations (Said).

In 1987, Said moved from the studio at the Academy to more spacious quarters in the Kreuzberg neighborhood, which abutted the still-extant Berlin wall.The frontier neighborhood attracted young immigrants, squatters, and the unemployed. It was portrayed in the media, and in the public eye as well, as a threatening place due to its concentration of far-left organizations and of nonresidents,mostly Gastarbeiter from Turkey. Even as it quenched the need for unskilled labor, the neighborhood evoked a primeval brand of xenophobia that mingled with feelings ranging from criminal to victim, exhuming evil spirits from the past as would a sorcerer and impeding the formation of a homogeneous social identity in West Germany (MacDougall, 168-175].

“Berlin,” Osama relates, “was not a typical German city. It abounded with young artists from all over the world; its orientation was Left and there were lots of demonstrations.Otherwise, I would not have survived there. In the early 1980s,I did not encounter neo-Nazis; all I knew were leftists, Turkish migrants,and other foreigners. The Germans whom I knew were ashamed of what the Nazis had done and respected foreigners. I didn't hear the word Auslander [foreigner] and I knew about the city's past. When I reached Berlin,I visited Teufelsberg (a hill made of evacuated rubble)and Checkpoint Charlie, and I watched films about the concentration camps and the artists whom the Nazis had persecuted. In Berlin I learned about the Holocaust and about a highly complex socio-political reality.”

In his new spacious studio, Said was able to produce a series of large works and develop the conceptual materialism that informs his oeuvre. One of his first creations, Child (1988), signaled the artistic path that Said had begun to follow.The characters in the paintings denote no one in particular; they represent Everyman. In contrast to an aesthetic of external detail that evokes someone specific,the figures in Said's opuses turn to a shadowy inner aesthetic. Contact with this aesthetic has to find expression in a color-filled surface-a person whose exact sex, male or female, cannot always be discerned."When one relies on external details, such as painstaking adherence to a prayer liturgy, one ends up with a dual morality.If you treat a container too cautiously, you will lose its contents.For me,religion is an abstract concept that reflects an inner content that acts for the collective welfare in order to avert harm"(Said).

Time and temporality

In Berlin, Said revealed his furrows of emotion, thought, and material technique in art. His most vital materials are his childhood memories of grandfather, grandmother,village, and tradition. They are sewn into him; they are the origins of personal histories, folktales, and mythologies (Said). Said's Child signifies the Postmodern path that he has taken.The crucial point of departure for understanding contemporary expression, Said states, is planted in the past. The past, in turn, is not merely a place of history. It harbors vitality, and the loss of that vitality amid the cogs of progress sounds an alarm for the future of humankind. The boy in the painting stands at the entrance to a house built of mortar; at his side is an olive tree.Although the painting concerns childhood and not an individual child, it is an autobiographical work retrieved from memory (Huyssen,2006, 78). Said's grandmother had decorated his boyhood home, it too a clay house, with things she had brought in from the field. In the winter, when he came home from his land-games, he undressed and rinsed himself off before entering the house as if performing a purification ritual. The mud that he scraped from his body with a flick of the hand accumulates at his feet. With his fingers Said reworked the area of the feet in the painting, half-touching the language of art with sensations of past and faith in the future. A tear wells from the eye of the naked boy who stands at the doorway to the traditional house next to the olive tree in a combined manifestation of roots and hope. "If the olive tree knew who had planted it, the oil would turn into tears," wrote Mahmoud Darwish about a light whose roots are planted in the past [Darwish, 1964, 26). The cyclical materiality, ancient and contemporary,is reflected in a delicate equilibrium of nature and civilization that have long existed in disequilibrium.The sculpture of the old fallah [peasant] lcast bronze, 1989), and the painting of the Boy in Berlin propose, in the face of a modern frantic and challenging technological ecology, an attentive ancient pace,born of a rural tradition,that progresses along the life cycle from the purity of childhood to the wisdom of old age (Huyssen, 1995,5). The Boy integrates ash,a vestige of the coal that Berliners used to heat their homes,with pigments intermixed with industrial acrylic. The coal ash, the asphalt, the waste, and the animal remains tap into steadily vanishing life cycle and shroud its modern alternative in doubt. As the poet says,

“...grandfather has awoken to collect the weeds from his vineyard underground,beneath the black street..." (Darwish, 2014,35).

The collision of the modern and the primeval in Darwish's poem denotes the inevitable encounter between the Arab world and the outcomes of the world that is perceived as First. The Palestinian narrative has a special place in this demarche because its tradition has been assimilated so mor dantly into the bosom of the First World, the leading world.

"The Nakba,”Said relates,“gave Palestinian art a more developed human depth than that of the other Arab states because the Palestinian diaspora that it produced is exposed to global art from many directions but meets at the same point. Everyone has a family that lost someone and I'm one of them.This is the spirit that carried me from the village where I was born to art studies, to life in Berlin until 1998, and from there back to Nahf, which by now has become a modern place. You are not like someone who was born and raised in one place. You wander about without knowing what each day will bring. It's not a daily affair;it's an inner sense of nomadism that surrounds you"(Said).

Loss causes life-tradition and the chain of memory to unravel, in the sense of "Here is a present which has no time, no one here has found any who remembers how we came out of the gate,like the wind, or at what time we tumbled out of yesterday, how yesterday was shattered on the pavement into pieces .." (Darwish, 2014, 10-11). Modern industrialization has smothered the wisdom of the sustainability that is attained by working the land. Progress has progressed in its arbitrary way and the Enlightenment squandered an oral acumen that had been passed on and woven in from generation to generation. Its scattered particles now yearn for a cultural volte-face in the picture of memory. The environmental blow strikes not only the body but also, and mainly,the spirit,which has lost its way in the sea of life,as in a 1991 painting of Poseidon.The author Abdul Rahman Munif sees the growth of the modern Arab novel as a cultural reaction to the Arabs' defeats in the hands of modernity as manifested since 1948 |Yahya,43].In the opening chapter of his novel Cities of Salt,Munif describes apremodern,pre-state era, in which a Bedouin community maintains its simple traditional waysand coexists peacefully with the oasis environment that it had inhabited until black gold was discovered.The novel recounts the traumatic social change that prodded traditional desert communities to move to exploitive towns and transformed traditional tribal rivalries into dictatorships' laws. Munif left Baghdad in the early 1980s and moved to a location near Paris where many Arab artists found refuge (Hafez, 10-11J.He did this to be able to write his book freely. Munif penned articles about plastic art and for many years maintained contact with Marwan,whose paintings and drawings illustrated the covers of his books from the mid-1990s onward. Invited to Berlin in 1992 to read excerpts of his books, Munif visited Marwan's studio. This led him to the studio of Said, his erstwhile pupil (Yahya, 106-107).

Three new works (2016) appear at the exhibition under the collective title "Stranger in the City of Salt," a gesture to Munif and to the modern context of art in the Arab world and the Middle East."The Stranger" lone of Said's early worksl and "Stranger in the City of Salt" meet up with "Bed of Sodom," one of several installations built especially for the exhibition."Bed of Sodom" depicts the trapping of the human legacy in a splint of modernity, dictatorship, and thirst for power. The stranger is the artist, whose work records a life of exile-within-exile-exile in modern Europe,exile from the police states of the Middle East,an exile that dredges up from the depths of the past a premodern human ethos in the service of a Postmodern chaos that descends into civil war, as in Syria. Said's three uncles who found refuge in Aleppo in 1948 now have to flee the city. Two paintings from 2016 appear at the exhibition under the title Skies over Aleppo. Despite their personal dimension, the works refine the frenzy of the war into a slender character inspired by Giacometti's sculptures. The weak line that expresses the image in the painting is squeezed between two fields of abstract color. They create the sense of destroyed streets by means of surfaces reworked in heavy strokes of color that recall the well-crafted abstraction in the works of Gerhard Richter (Harten, 284-287).Giacometti,Richter, and the return to painting in the 1970s and 1980s are modern tools with which Said invokes Postmodernism to unpack formulas that buffer between the First World and the Third.

Ghostly images

The modern context of art was based on a close fit between the avant-garde as the formulator of a new art language and its manifestation in the service of specific cultural foci (Huyssen, 1984:40). The processes invoked by a certain group to create a modern global art language are integrated into the consolidation of the Western city as a locus of global rule. One may liken it to a metropolis that shapes a perception of progress and creates a gap between a "high,"i.e., new, state of affairs and an ostensibly marginal and "low" situation. In the evolution of the language of modern art in its Euro-American setting-the so-called First World-cultural achievement is bound up with economic supremacy and social polarization between the countries of the First World and those of the Third. The disparity between the Old World countries and those that had to wait until the twentieth century for the privilege of independence reinforced a colonial model of relations between protector and protégé states. Having to adapt to the ways of modern governance in the economic and structural senses, the new states also imitated the old in their cultural establishments. The leading countries' economic edge in the 1950s and 1960s, coupled with an avant-garde that espoused art for art's sake, masked the construction of cultural bridges between developed and developing countries. The internal exhaustion of the modern language and the development of the new states' self-identity upset the modern equilibrium and created a possibility of a different relationship.The failure of the modern utopias and the decline in the revolutionary value of the avant-garde weakened the traditional concentration that had evolved in the modern era and created a Postmodern malaise (Huyssen,1984:9). The new topography of contemporary art entailed a different self-integration into the socio-geographic and historical circumstances of the global world. The process of defining art has shed its total dependency on the West and has tied into a new social and political reality, a global one.The new circumstances of artistic endeavor dictate a demarche in the opposite direction of the pace of modern growth. In the accelerated time of progress and innovation, processes of deconstruction, decomposition, and deceleration occur continually. In lieu of a universal conceptual focus, structural decentralization is taking place. The cultural codes operate disharmoniously as a whole set of historical tenses is put to versatile use. Modern language is unraveling and joining, as one possibility, a global field of endeavor in which the revolutionary pace gives way to lost time and repressed fringes. The current image of marginality is no longer one of a small groups but of broad,semi-peripheral ones in which modern cultural creativity has been diverted from modern ambition (de Certeau:xi-xvii).

The binomial of developed versus developing countries operates in a continual state of economic and social friction, one that carries the potential of a confrontation between the strong and the weak and between center and periphery. The economic and demographic changes produced by this friction generate a state of semi-peripherality, in which individuals and groups in different places in the modern arena amass social, political, and cultural baggage that befits a Postmodern reality. The semi-peripheral profile is associated chiefly with migration, nomadism,and transition from a Third World situation to global Modernism (Steinitz). The new universality of contemporary art links to a delicate dialectic between a parochial "I" and the total accumulation of knowledge of the history of art. The turning point in defining the principal centers of art reorders relations between the local and the international and between the superior and the inferior.They self-organize within the context of criticism of the First World and new opportunities to present contents of Third World origin. The characteristic polarity of a semi-peripheral situation manifests in a sensitivity that tolerates both modern and premodern worlds. This sensitivity crosses political fields and works through their meaning on the basis of personal experience with the latent sense of fringeness that the semi-peripheral in-between zones sustain over time.

This observation gives the semi-peripheral situation a role to play in gradually changing the modern sense of time,innovation,and progress and in the turning point in sociological, philosophical, and cultural inequality that is coming about. The semi-peripheral space of time accommodates alternative composites of outlook in which historical and environmental elements contradict modern intensity and efficiency and augment them with identities that sufferedfrom diminished importance in their modern stage. For this reason,Postmodernism no longer reflects evolution in the internal modern struggle. Today's Postmodern sensitivity differs from Modernism and the avant-garde in that it evokes historical questions about cultural traditions and their preservation (Huyssen,1984:48|. Standing up against the dictates of continuity and pace, as Said does with his artistic materials in Land Work, corroborates traits that were discarded in the modern stage, allowing attention to be paid to repressed segments of reality that continue to exist in Third World territories and migrant neighborhoods in great Western cities. Esra Özyürek, in her book about nostalgia for modernity in daily life and politics in Turkey, describes how the development of modernity yielded different interpretations in different communities and regions. Despite the many complexions that modernity was given,strong central faith in its constant formula thwarted a discourse of interpretations among different peripheries. Özyürek proposes, as an alternative, a "nostalgic modernity" that, while liberated from mobilized modernity, does not aspire to tear it down lÖzyürek: 19). This semi-peripheral model is geared to temporary perspectives that derive inspiration from long-enduring cultural and historical influences-local and international,Western and Eastern,ancient and contemporary.

In Svetlana Boym's view, a critical nostalgia of this kind should be perceived not as opposed to modernity but as outflanking it-a circumvention that does not abrogate the utopian aspiration but creates a turning point in understanding its structure of imagined time. In this watershed, time is perceived not as something to exhaust purposefully in the service of progress and perfection but rather as a multi-complexioned integration of combinations. The circumvention to which Boym refers reflects a reflective, hopeful kind of nostalgia thatdoes not busy itself with restoring a bygone reality. Its manifestations appear in descriptions of strata of time, ruins, and blights thatattest to a contradiction that exists in Modernism between innovation and enlightenment, on the one hand,and extreme destructiveness on the other (Boym, 2001:30, 45). Said produced his paintings "Flight" (1989), "Hewn" (1990), and a series of depictions of fallen trees in Berlin shortly before and after the city's unification. The nostalgia for the former East Germany that has developed since 1989 attests to the relationship between nostalgia and schisms in personal and collective life (Abdullah, 2012: 208). In the 1980s and 1990sin Berlin,the Postmodern watershed at which off-putting revolutionism turned soberly to a more global historical dimension was crossed with growing strength (Huyssen, 1995: 1). This allowed Said to assimilate universal human meaning, originating in the loss in the Middle East, into contemporary painting. Nostalgia derives its social value from its ability to establish a stable sense of time that is helpful in bridging over a crisis,tolerating the questionable present, and coping with a vague future (Davis, 1979: 49). In 1940, as he fled from the Nazis, Walter Benjamin wrote theses about the concept of history.Paul Klee's monoprint "Angelus Novus" is described in these theses as an angel who finds it difficult to turn away from a spectacle that has captured his gaze. His gaping eyes and mouth cry out at the sight of past disasters that mass steadily and inexorably at his feet. He wants to stop, say something about the dead, and set the crises right. A storm blowing in from the Garden of Eden,however,breathes violently into his wings, propelling him backwards into the future even as the heap of past crises continues to accumulate to high heaven.The tempest is a microcosm of progress (Benjamin, 257-258). Modernity,Boym points out, began with utopia and ended with nostalgia. Optimistic faith in the future has lost its meaning whereas nostalgia, for better or worse,survives and in some mysterious way remains contemporary.Nostalgia is not a mere yearning for a place but rather an expression of understanding the dimension of time and space as a possibility of crossing the lines that separate the "parochial" from the "international." Nostalgia resembles yearning for a place but expresses a craving for a different time,one of childhood and of a slower pace of dreams (Huyssen, 1995: 3-5). Broadly speaking, nostalgia rebels against modern time's perception of progress. It aspires to render time into a personal or collective mythology that allows one to oscillate back and forth, like motion in in the work itself. Adunis opposes those who reject the West but does not flinch from criticizing it:

We should spurn the West only when it maintains a colonialist ideology. To reject its mechanization and technology does not mean rejecting the intellectual process that fathered them. We oppose the way it forces its technology on us [..].

Adunis sees creativity as a material part of the East and, contrastingly,regards Western capability as essentially technical. Thus in effect, he argues, creative progress in the West is of Eastern origin. Visiting Said's studio in Berlin,Adunis observed his Land Work and handed him an autographed volume of his poetry. Adunis' thinking imparts an additional meaning, from East to West, to the Land Work that Said created as a reflexive nostalgia-a meaning that changes the tick-tock of modern time. Adunis writes:

Technical ability is progress in copying over a known model. Creative ability is not technical progress. [...] It is an emanation-an infinite discovery of essence. In terms of the ability to create [...] in the most profound and human sense, the West has nothing that has not been appropriated from the East. Religion,philosophy, poetry (art at large)-all are Eastern at source and so are all the artists in these fields, from Dante to the present day. The unmistakable trademark of the West is technical ability, not creative ability. Therefore,from a cultural point of view,we may say that the West is the son of the East,except that this son is a baby whose parents have abandoned him: deviation,exploitation, control,colonialism, imperialism; in other words, rebelling against Father. Furthermore,the West no longer settles for rebellion; it wants to kill its father.[...] For this reason,the great works of the West [...]transcended the technical plane onto the other plane, that is, their wellsprings are Eastern [...] (Adunis, 18-55).

February 2017

Bibliography

Abdullah,H.(2012),"New German Painting, Painting, Nostalgia & Cultural Identity in Post-Unification Germany,"dissertation submitted to the Department of Sociology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy,London. Adunis (2013), Key to the Acts of the Spirit,trans. from the Arabic into Hebrew by Reuven Snir,Keshev le-Shira.

Benjamin,W.[1968],llluminations,Schocken Books.

Ben-Zvi,T.(2009), Men in the Sun, Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art lin Hebrewl.

Ben-Zvi, T.(2010),Abed Abadi, Fifty Years of Art, Umm al-Fahm Art Gallery lin Hebrew).

Boym,S.(2001), The Future of Nostalgia, New York:Basic Books.

Boym,S. (2007),"Nostalgia and Its Discontents,"Hedgehog Review 9.2 (2007) pp. 7-18.

Buck-Morss, S.(2000),Dreamworld and Catastrophe:the Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West, MIT Press.

Bulata,K. (1990), "Israeli and Palestinian Artists:Facing the Forests," Kav 10 lin Hebrewl, pp. 170-175.

Caspi, D., and Kabha, M. (2001), "From Holy Jerusalem to the Spring,"Panim-Culture,Society,and Education 16,March lin Hebrewl.

Darwish,M.(1964),Olive Leaves,Awraq al-Zaitoun,Beirut,Dar El-Awdah (in Arabic) Darwish, M.(2014], Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone? translation from the Arabic by Mohammad Shaheen,London:Hesperus Press Limited.

Davis, F.(1979), Yearning for Yesterday:A Sociology of Nostalgia,New York: Free Press;London: Collier Macmillan.

De Certeau,M.(1984),The Practice of Everyday Life,trans.Steven Rendall,Berkeley, CA:University of California Press.

Hafez,S.(2006), "Munif, a Bio-History,"The New Left Review 37, January February.

Harten,J.(1986),Gerhard Richter,Paintings,DuMont Buchverlag.

Huyssen, A. [1984], "Mapping the Postmodern," New German Critique, No. 33, Autumn,pp.5 52.

Huyssen,A.(1995],Twilight Memories,Routledge.

Huyssen,A. (2006), "Nostalgia for Ruins," Grey Room, No.23, Spring, pp. 6-21, MIT Press.

Huyssen, A. (2010), "German Painting in the ColdWar," New German Critique 110, Vol.37, No. 2, Summer.

Jamal,A.(2009), in Ben-Zvi,Men in the Sun.

Kimmerling, B., and Migdal, Y.S. (1999), The Palestinians: A People in Formation, Jerusalem: Keter [in Hebrew].

MacDougall, E.C. (2011), "Cold War Capital: Contested Urbanity in West Berlin, 1963-1989," Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School- Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey,New Brunswick.

Özyürek, E. (2006), Nostalgia for the Modern: State Secularism and Everyday Politics in Turkey, Duke University Press.

Said, 0.(2016),recorded interview for exhibition: Land Work-Materials of Time in the Works of Osama Said,Afula Municipal Art Gallery, April-June 2017 (in Hebrew). Stiassny, N.,"Art in East Germany (GDR):Exclusion of the East German Field of Art from the Art History Discourse," Proceedings in Historyand Theory,Bezalel//,No.29, retrieved from https://bezalel.secured.co.il/zope/home/en/1376936935/1386399486 Yahya, M., ed. (2007], "Writing a Tool for Change, Abd al Rahaman Munif Remembered," The MIT Electronic Journal of Middle East Studies,7,Spring.